By Parisa Hafezi

DUBAI (Reuters) -Iran’s hanging of protesters — and display of their lifeless bodies suspended from cranes — seems to have instilled enough fear to keep people off the streets after months of anti-government unrest.

The success of the crackdown on the worst political turmoil in years is likely to reinforce a view among Iran’s hardline rulers that suppression of dissent is the way to keep power.

The achievement may prove shortlived, however, according analysts and experts who spoke to Reuters. They argue the resort to deadly state violence is merely pushing dissent underground, while deepening anger felt by ordinary Iranians about the clerical establishment that has ruled them for four decades.

“It has been relatively successful since the number of people on the streets has decreased,” said Saeid Golkar of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, referring to the crackdown and executions.

“However, it has created a massive resentment among Iranians.”

Executive Director at the Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, Hadi Ghaemi said the establishment’s main focus was to intimidate the population into submission by any means.

“Protests have taken a different shape, but not ended. People are either in prison or they have gone underground because they are determined to find a way to keep fighting,” he said.

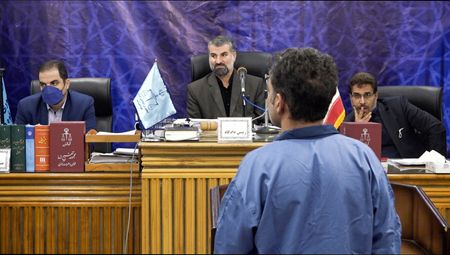

Defying public fury and international criticism, Iran has handed down dozens of death sentences to intimidate Iranians enraged by the death of Iranian-Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini, 22.

Her death in the custody of morality police in September 2022 unleashed years of pent up anger in society, over issues ranging from economic misery and discrimination against ethnic minorities to tightening social and political controls.

At least four people have been hanged since the demonstrations started, according to the judiciary, including two protesters on Saturday for allegedly killing a member of the volunteer Basij militia forces.

Amnesty International said last month Iranian authorities are seeking the death penalty for at least 26 others in what it called “sham trials designed to intimidate protesters”.

The moves reflect what experts say is the religious leadership’s consistent approach to government ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that brought it to power — a readiness to use whatever force is needed to crush dissent.

“The regime’s primary strategy has always been victory through terrorizing. Suppression is the regime’s only solution since it is incompetent and incapable of change or good governance,” said Golkar.

ECONOMIC MISERY

Protests, which have slowed considerably since the hangings began, have been at their most intense in the Sunni-populated areas of Iran and are currently mostly limited to those regions.

And yet, the analysts said, a revolutionary spirit that managed to take root across the country during the months of protest may yet survive the security crackdown — not least because the protesters’ grievances remain unaddressed.

With deepening economic misery, largely because of U.S. sanctions over Tehran’s disputed nuclear work, many Iranians are feeling the pain of galloping inflation and rising joblessness.

Inflation has soared to over 50%, the highest level in decades. Youth unemployment remains high with over 50% of Iranians being pushed below the poverty line, according to reports by Iran’s Statistics Center.

“There is no turning point (back to the status quo), and the regime cannot go back to the era before Mahsa’s death,” Ghaemi said.

Alex Vatanka, director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, said Tehran was banking on repression and violence as its way out of this crisis.

“This might work in the short term but … it won’t work in the long term,” Vatanka said, citing reasons such as Iran’s deteriorating economy and its fearless young population who want “big political change, and they will fight for it.”

There are no signs that President Ebrahim Raisi or other leaders are trying to come up with fresh policies to try and win over the public. Instead, their attention appears to be fixed on security.

The clerical leadership appears worried that exercising restraint over protesters could make them look weak among their political and paramilitary supporters, the analysts said.

Reuters could not reach officials at Raisi’s office for comment.

Golkar said an additional motive for the executions was the leadership’s need to satisfy core supporters in organisations like the Basij, the volunteer militia that has been instrumental at countering the spontaneous and leaderless unrest.

KHAMENEI BACKS CRACKDOWN

“The regime wants to message its supporters that it will support them by all means,” Golkar said.

To send shockwaves, the authorities imposed travel bans and jail terms on several public figures from athletes to artists and rappers. A karate champion was among those executed.

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Monday signalled the state has no intention of softening its crackdown, saying in a televised speech that those who “set fire to public places have committed treason with no doubt”.

Wielding uncompromising state power has been a central theme of Raisi’s career. He is under U.S. sanctions over a past that includes what the United States and activists say was his role overseeing the killings of thousands of political prisoners in the 1980s.

When asked about those 1980s killings, Raisi told reporters shortly after his election in 2021 that he should be praised for defending the security of the people.

Ghaemi said the main officials pushing for the executions today were deeply involved in the 1980s killings of prisoners.

“But this is not the 1980s when they carried all those crimes in darkness,” he said. “Everything they do gets on social media and attracts huge international attention.”

(Writing by Parisa HafeziEditing by Michael Georgy, William Maclean)