By Phil Stewart and Michelle Nichols

NEW YORK/WASHINGTON (Reuters) – The surprise deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia to restore diplomatic ties offers much for the United States to be intrigued about, including a possible path to rein in Tehran’s nuclear program and a chance to cement a ceasefire in Yemen.

It also contains an element sure to make officials in Washington deeply uneasy – the role of China as peace broker in a region where the U.S. has long wielded influence.

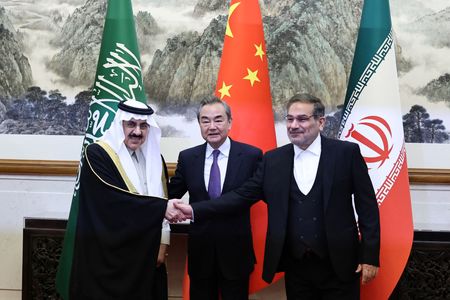

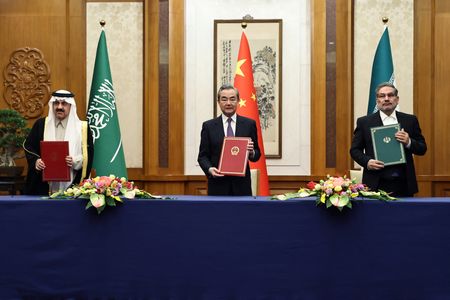

The deal was announced after four days of previously undisclosed talks in Beijing between the Middle East rivals. White House spokesperson John Kirby said on Friday that while Washington was not directly involved, Saudi Arabia kept U.S. officials informed of the talks with Iran.

Relations between the U.S. and China have become highly contentious over issues ranging from trade to espionage and increasingly the two powers compete for influence in parts of the world far from their own borders.

Kirby appeared to downplay China’s involvement in Friday’s development, saying the White House believes internal and external pressure, including effective Saudi deterrence against attacks from Iran or its proxies, ultimately brought Tehran to the table.

But former senior U.S. and U.N. official Jeffrey Feltman said China’s role, rather than the re-opening of embassies after six years, was the most significant aspect of the agreement.

“This will be interpreted – probably accurately – as a slap at the Biden administration and as evidence that China is the rising power,” said Feltman, a fellow at the Brookings Institution.

NUCLEAR TALKS

The agreement comes as Iran accelerates its nuclear program after two years of failed U.S. attempts to revive a 2015 deal that aimed to stop Tehran producing a nuclear bomb.

Those efforts have been complicated by a violent crackdown by Iranian authorities on protests and tough U.S. sanctions on Tehran over accusations of human rights abuses.

Brian Katulis, of the Middle East Institute, said that for the U.S. and Israel the agreement offers a “new possible pathway” for reviving stalled talks on the Iran nuclear issue, with a potential partner in Riyadh.

“Saudi Arabia is deeply concerned about Iran’s nuclear program,” he said. “If this new opening between Iran and Saudi Arabia is going to be meaningful and impactful, it will have to address the concerns about Iran’s nuclear program – otherwise the opening is just optics.”

Friday’s agreement also offers hope for more durable peace in Yemen, where a conflict sparked in 2014 has widely been seen as a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

A U.N.-brokered truce agreed last April has largely held despite expiring in October without agreement between the parties to extend it.

Gerald Fierestein, a former U.S. ambassador to Yemen, said Riyadh would “not have gone along with this without getting something, whether that something is Yemen or something else is harder to see.”

GROWING ROLE FOR CHINA

China’s involvement in brokering the deal could have “significant implications” for Washington, said Daniel Russel, the top U.S. diplomat for East Asia under former President Barack Obama.

Russel said it was unusual for China to act on its own to help broker a diplomatic deal in a dispute to which it was not a party.

“The question is, whether this is the shape of things to come?” he said. “Could it be a precursor to a Chinese mediation effort between Russia and Ukraine when Xi visits Moscow?”

When it comes to Iran, it is not clear that the results will be good for the U.S., said Naysan Rafati, senior Iran analyst at International Crisis Group.

“The drawback is that at a time when Washington and Western partners are increasing pressure against the Islamic Republic … Tehran will believe it can break its isolation and, given the Chinese role, draw on major-power cover,” said Rafati.

China’s involvement has already drawn skepticism in Washington about Beijing’s motives.

Republican Representative Michael McCaul, chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, rejected China’s portrayal of itself as peace-broker, saying it “is not a responsible stakeholder and cannot be trusted as a fair or impartial mediator.”

Kirby said the U.S. was closely monitoring Beijing’s behavior in the Middle East and elsewhere.

“As for Chinese influence there or in Africa or Latin America, it’s not like we have blinders on,” he said. “We certainly continue to watch China as they try to gain influence and footholds elsewhere around the world in their own selfish interests.”

Still, Beijing’s involvement adds to a perception of growing Chinese power and influence that contributes to a narrative of a shrinking U.S. global presence, said Jon Alterman, of Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“The not-so-subtle message that China is sending is that while the United States is the preponderant military power in the Gulf, China is a powerful and arguably rising diplomatic presence,” he said.

(Additional reporting by Patricia Zengerle, Jonathan Landay and David Brunnstrom; Writing by Michelle Nichols; Editing by Don Durfee and Daniel Wallis)