By Nichola Groom

(Reuters) – The Solar Star project in California is among the largest solar energy facilities in the world, boasting 1.7 million panels spread over 3,000 acres north of Los Angeles. Its gargantuan scale points to an uncomfortable fact for the industry: a natural gas power plant 100 miles south produces the same amount of energy on just 122 acres.

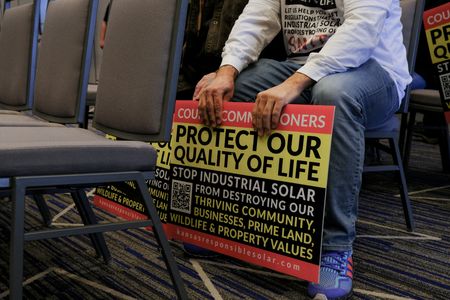

The dynamic encapsulates the industry’s biggest obstacle to growth: Solar farms require huge amounts of land, and there’s a fast-growing movement, fueled by politicized social-media campaigns, to prevent solar developers from permitting new sites in rural America.

That’s a major problem for the transition away from fossil fuels to combat climate change. Solar currently makes up 3% of U.S. electricity supply and could reach 45% by 2050 to meet the Biden administration’s goals to eliminate or offset emissions by 2050, according to the Department of Energy. To get there, the U.S. solar industry needs a land area twice the size of Massachusetts, according to DOE. And not any land will do, either. It needs to be flat, dry, sunny, and near transmission infrastructure that will transport its power to market. (See graphic compare solar land use with other energy sources:

As solar developers propose new, often sprawling projects in places like Kansas, Maine, Texas, Virginia and elsewhere, local governments and activist groups are seeking to block them and often succeeding. They cite reasons ranging from aesthetics that would harm property values to fears about health and safety, and loss of arable land, farm culture, or wildlife habitat.

“This is increasingly one of the top barriers that we’re going to face,” said Steve Kalland, executive director of the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center, a research center that supports clean energy development nationwide. “If we can’t get projects sited and deployed, then we’re going to have real problems on our hands.”

Officials at the White House and the Department of Energy, who are pushing for a rapid expansion of solar power, did not comment on the industry’s land-acquisition problems.

In most cases, the opposition to these projects is being organized on Facebook, where the number of pages devoted to blocking solar development has exploded in recent years. The pages air a mix of legitimate concerns, such as the loss of scenic vistas, tree removal, and soil erosion, with misinformation about climate change and alleged health hazards from solar electricity. The false claims include arguments that climate change is a hoax to groundless assertions that solar farms leach the carcinogen cadmium into the soil and nearby waterways when it rains, or that they rarely produce electricity.

Reuters identified 45 groups or pages on Facebook dedicated to opposing large solar projects, with names such as “No Solar in Our Backyards!” and “Stop Solar Farms.” Only nine existed prior to 2020, and nearly half were created in 2021. The groups together boast nearly 20,000 members.

“For every single large-scale solar project, you’re seeing very well-organized opposition on social media,” said Matthew Sahd, a solar market analyst for energy research firm Wood Mackenzie. “It’s very impressive what these local communities are able to organize.”

Beth Snider, of Virginia’s Page County Citizens for Responsible Solar, said she believes solar developers are using the climate change issue to justify profit-making businesses that hurt the environment in other ways.

“The solar companies don’t care about the environment – the farmland, and the rural communities they will destroy to get these projects,” she said. “They are all about the money.”

Construction of the first large solar projects, including Solar Star, completed in 2015, drew little opposition. They were sited mostly in remote areas such as the California desert. Now, tensions are rising as the sector plans bigger projects and reaches into more populated rural areas unfamiliar with solar.

The industry is expanding rapidly with government and corporate backing, and seeking permits or zoning revisions from county and town boards that oversee land use in residential neighborhoods and farmlands. Often, they are in politically conservative regions where citizens are less concerned about climate change and more supportive of fossil-fuel industries and jobs.

Their protests are persuasive. More than 1.7 gigawatts of proposed solar capacity was canceled during the permitting stage in 2021, according to an analysis by Wood Mackenzie conducted for Reuters. That’s equivalent to a tenth of the 17 gigawatts of utility-scale solar capacity installed in the United States last year. Wood Mackenzie did not track the data on permitting prior to 2021.

Those figures do not account for the potential projects that have been preempted by locally imposed limitations or moratoria on solar applications. An analysis by Columbia Law School last year found 103 localities nationwide that have adopted policies to block or restrict renewable energy development – a list the report said is not exhaustive.

The American Clean Power Association, an industry trade group, said in a statement that the protests present a major challenge to the solar industry and threaten its role in addressing climate damage.

“Community concerns have made it harder for some developers to scale solar projects at the rate that science dictates that we need to,” said David Murray, ACP’s director of solar policy.

Site acquisition is at the top of the U.S. solar industry’s list of threats to growth. In a poll of 44 developers last year by clean energy marketplace LevelTen Energy, 52% said permitting challenges were among the top three barriers to achieving the nation’s solar energy goals and nearly 20% called out land availability. Other challenges included access to transmission lines and supply-chain disruptions.

“It’s pretty obvious that, if there’s a climate urgency, we’re not behaving that way,” said Armond Cohen, executive director of environmental group Clean Air Task Force. “There’s this assumption that there’s so much solar and wind available at such low cost, it’s obviously going to get built… maybe it will, but something pretty serious is going to have to change.”

ONLINE OFFENSE

Carrie Brandon’s home sits near the proposed site for a 2,000-plus-acre solar farm that renewable-energy behemoth NextEra hopes to build at the border of Kansas’ Douglas and Johnson counties. When she heard about the planned 320-megawatt project, Brandon leapt into action to stop it. She hired a consultant, sent petitions to neighbors and produced a YouTube channel and Facebook site under the name Kansans for Responsible Solar.

“That’s not what we signed up for,” Brandon said, noting that she and her husband built their dream home on 40 acres in Douglas County in 2018.

Brandon says she does not oppose green energy but believes solar projects belong in places such as former industrial sites or on rooftops. She worries about her property value but said her primary concern is the health and safety of people residing nearby. She said she worries that herbicides on the site, used to prevent vegetation from growing on panels, could contaminate ponds and groundwater. She also said solar panels raise the risk of fires and health problems from exposure to electromagnetic fields.

“It’s not about looking at it,” she said. “It’s about the health impacts.”

Researchers have found no evidence to support increased fire risk or health concerns from solar panels.

Brandon found an ally in Kansas State Senator Mike Thompson, a Republican who has been criticized for spreading misinformation about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines and the science behind climate change.

“Why are we investing in all of these renewable sources of energy? A lot of people will say it’s because we’ve got to combat climate change. And that is one of the biggest scams out there,” Thompson, a former TV weatherman who chairs the Senate’s utilities committee, said in a video on one of Brandon’s sites.

Thompson did not respond to a request for comment.

Brandon says she considers some of the contributions on her group’s Facebook page extreme but does not censor them. “I find opposing points of view to be stimulating conversation,” she said.

The impact of Brandon’s group is being tested as Johnson County crafts zoning rules for large solar facilities that could determine the fate of the NextEra project. Planning officials initially drafted what would have been among the most restrictive rules for solar facilities in the nation – limiting leasing terms to a maximum 20 years and capping acreage at 1,000 acres – but were directed by a county board this week to reconsider their proposal next month.

NextEra’s project is designed to last 30 years, and the company has already leased more than 2,000 acres of land.

A NextEra spokesperson did not comment on the opposition to its projects.

The Virginia solar protest group led by Beth Snider, in Page County, also uses Facebook to organize against solar development. Their focus is a 500-acre project in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley by Urban Grid, a unit of Canada’s Brookfield Renewable, one of the world’s top renewable energy asset owners. Snider, who lives near the proposed site, worries it will mar the landscape.

Posts by her group’s more than 500 members include wide-ranging criticisms of all kinds of renewable energy. One post included photos of solar panels in Arizona covered in snow and not producing electricity. Another cited a post from the climate change skeptic blog NoTricksZone saying that EV owners in Germany can barely afford to charge their vehicles because of surging electricity prices there.

The group brought an overflow crowd earlier this year to a planning meeting. After 33 people testified against the project – none in favor – the four-member panel voted unanimously to recommend rejection of the project by the county Board of Supervisors, which has a year to take up the application. Urban Grid would not comment on the project.

In central Texas, meanwhile, school district and county officials in at least four counties this year have dealt blows to solar development by refusing the requests of developers for tax breaks intended to ensure the projects are economical.

The projects would have generated millions in tax revenue over decades. Local officials, however, were convinced by arguments made by local residents on Facebook and in public meetings that the projects would undermine the region’s rural culture and create few jobs.

“They call themselves solar ‘farms,’ which is irritating to me,” Ron Pack, a landowner in Erath County, Texas, said in an interview. “They give the indication that it’s all bunny rabbits and butterflies over there. And it’s not. It’s 2,400 acres of total destruction.”

Pack, whose property is adjacent to where NextEra is planning a 225-megawatt solar plant, worries about soil erosion under the panels polluting the water of the nearby Bosque River.

Solar developers must often clear land of trees and other vegetation before they install their equipment to ensure the panels have unobstructed access to sunlight, which has in some cases led to erosion during heavy rains.

NextEra did not respond to requests for comment. On the project website, the company says: “No form of energy is free from environmental impact; however, solar energy has among the lowest impacts as it emits no air or water pollution.”

NEW FRONT IN THE CULTURE WARS

The protests reflect declining support for renewables nationwide.

A Pew Research Center poll this year showed 69% of U.S. adults favored developing alternatives to fossil fuels, down from 79% two years ago. The drop came almost entirely from respondents on the political right, with just 43% of Republicans or those who lean Republican saying they support alternative energy development compared with 65% in 2020.

Joshua Fergen, a sociologist who has studied rural attitudes toward renewable energy development, said solar power has transformed into a subject of the U.S. culture war – a politically divisive issue along the lines of vaccine mandates, police reform or abortion.

“You can’t divorce what you see on these anti-renewable Facebook groups from the larger political context,” he said.

Residents of liberal-leaning areas, however, have also organized against large-scale solar installations.

Alameda County, a San Francisco Bay area Democratic stronghold, for example, is considering more restrictive solar policies after residents sued over the approval of a 100-megawatt project in a rural valley over concerns about the visual and environmental impact.

UTILITIES SQUEEZED

Local pushback could delay plans by utilities to retire aging coal plants and replace them with solar projects to appease climate-conscious investors and regulators.

The Northern Indiana Public Service Co (NIPSCO), for instance, plans to retire more than 2 gigawatts of coal and gas-fired generation by 2028, replacing it with wind and solar. But one of the solar projects it had planned to start operating this year, a 200-megawatt facility in Boone County, was rejected last year by two separate local boards after residents organized against it, decrying the loss of farmland and rural culture, as well as the impact on views and local property values.

NIPSCO told Reuters that it continues trying to make the project work and remains confident about its broader clean-energy transition plan.

The difficulty finding workable solar project sites has led developers to pump up their bids for available land. Solar developers have been offering around $1,000 an acre for suitable land nationwide, far more than the $200 or so an acre landowners would get from a tenant farmer, according to Nathan Fabrick, executive vice president of solar for National Land Realty, a real estate brokerage that specializes in rural land.

“We get so many calls from landowners that are interested,” he said.

It’s a harder sell to communities as a whole, which often see little economic upside to offset the downsides of large installations, which often create only one or two full-time jobs.

The solar industry in some places has worked to make projects more palatable to the public. New Jersey, for instance, became a major market for solar despite the state’s dense development, primarily by putting projects on landfills or other disturbed land. And Minnesota has voluntary standards that encourage establishing pollinator-friendly vegetation at solar sites to reduce environmental opposition. Such projects help dissuade local concerns about solar farms, according to the DOE.

The Land & Liberty Coalition – a pro-solar group backed by donors associated with the political left, such as the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and MacArthur Foundation – is also trying to improve the solar industry’s chances by appealing to libertarian values. The coalition argues, for instance, that private landowners should be allowed to strike deals with developers without obstruction.

“Nobody ought to tell you, within reason of course, what you can and can’t do with your land,” said Tyler Duvelius, a spokesperson for the coalition.

The group has set up satellite offices in several states where battles over solar are raging, including Virginia, Indiana and Wisconsin, he said.

Landowners like Robert and Donna Knoche agree with the Land & Liberty Coalition’s arguments. The couple has an agreement with NextEra for its Johnson County project in Kansas to lease hundreds of acres that have been in the family for generations, and they are hoping their neighbors don’t ruin their opportunity to make some money from it.

“Our six children, none of them are farmers,” Robert Knoche, 94, said in an interview. “They’d probably get along better with NextEra than they would farming it.”

(Reporting by Nichola Groom; editing by Richard Valdmanis and Brian Thevenot)